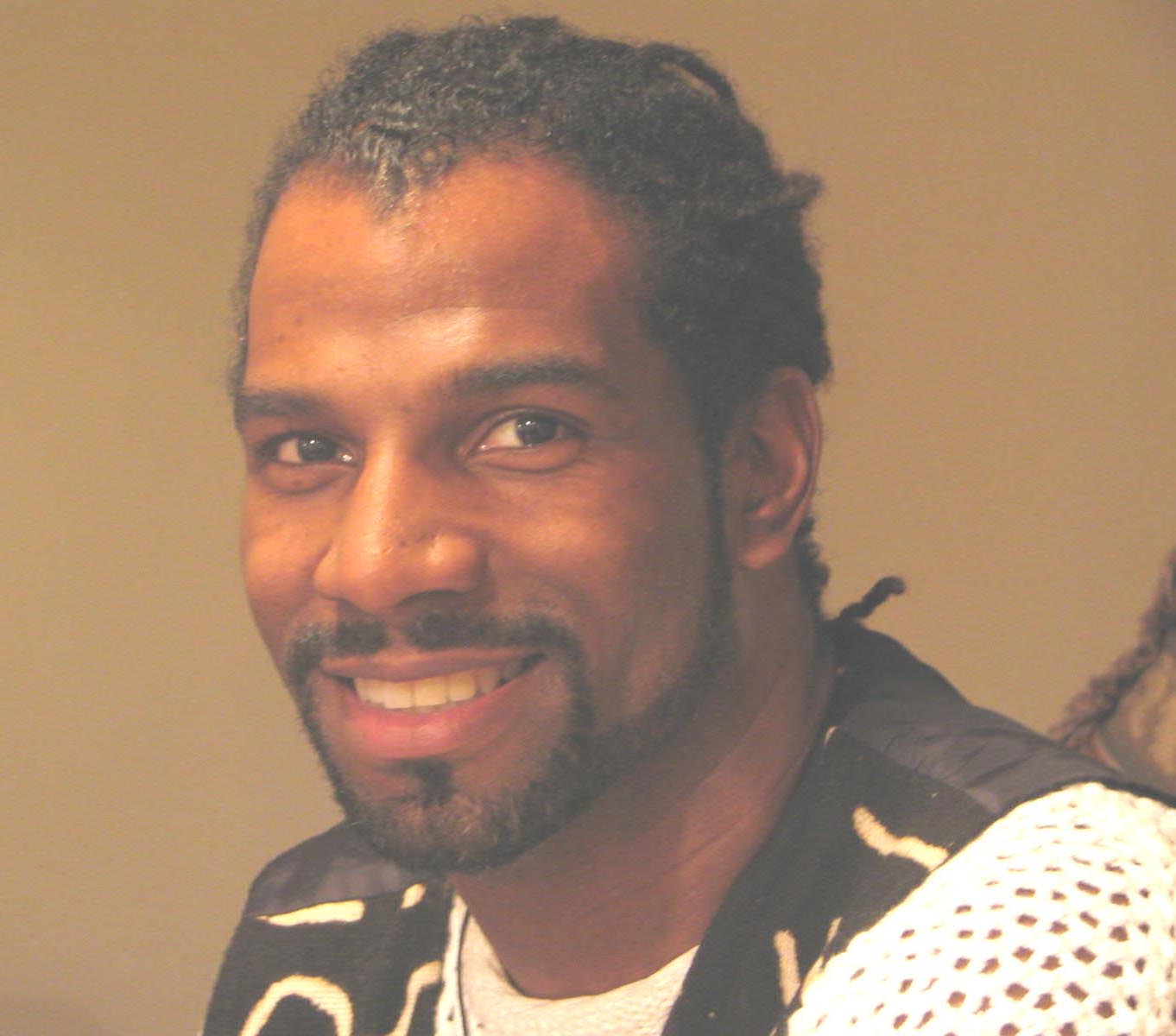

Interview with Darren T. WellsPresidential Award for Elementary Science Teaching, 2004 |

|

Darren T. Wells is a science teacher at J.P. Timilty School in Boston, Mass. He has been involved with several community organizations, including Concerned Black Men of Massachusetts at Northeastern University; the Sally Ride Science Club at MIT; other university projects at Boston University, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Tufts University; and partnerships with Massachusetts General Hospital and the Bell Foundation. He has received the Ambassadors in Education Award from the MetLife Foundation in recognition of his community involvement.

How did you get started in establishing community relations?

I have been volunteering in the community since my undergraduate days. I try to be involved in many ways: bike riding for charity, sitting on educational boards and committees, participating in tutoring and mentoring programs sponsored by community-based organizations. By pursuing my interests, and meeting many kinds of people in the process, benefits continue to come to my students.

What community-based work have you developed and how did you get support?

Rather than create school-based tasks for which entities in the community are asked to volunteer or contribute, I become involved with the groups on their terms. Much of what they need to accomplish might not occur without an educator participating. I work with them on their projects. After time, I find myself within a large network of people who are interested in supporting my work as well. Within that network will be resources for my students when need arises. As I volunteer to serve on community boards or engage in personal learning experiences, valuable contacts with resources emerge, whether in-kind, or as cash grants. For example, my participation in activities of a civic organization in my school’s neighborhood led to my students showcasing their understanding of the effects of fuel emission of buses and how it directly correlates to a disproportional increase in asthma rates among youth in Boston, now the highest in the state. Another example: At the University of Massachusetts Boston, a watershed program for teachers led to opportunities for students to investigate aquatic environmental issues. Also, by advising on projects conducted by and for Boston University, I was able to arrange for graduate students to work with my students on engineering and integrated science through the university’s community service program entitled “Wizard.” The exchange of favors is reciprocal, however. Sometimes associates who serve with you on community boards will on occasion invite you into their other programs. The network grows, but the price for this kind of networking can be a high demand on your evenings and weekends.

What advice would you give a teacher who wants to establish community connections?

Surprisingly, my advice is to start with your weaknesses. By that I mean you should identify whatever is not your strength, and recognize the things you need to be exposed to or learn. They can also be things you simply want to learn because of personal interests. Go for the free workshop or other learning experiences related to those needs. I have a strong background in biology, but am not so strong in literature. However, I am interested in the field, so I opt to go for the different experience, seeking to learn what I am weak in. This leads to new experiences through education institutions or other organizations in the community. There are many unfamiliar things to learn about in the community, and new things you can do in the community. Substantive benefits for your students will come from these. For example, my interest in working with one community group led to an opportunity for some of my students to travel throughout the state to present their science fair project and compete in a robotics competition.

How do you juggle your teaching responsibilities with the community partnerships?

Networking with and volunteering for organizations that are potential community resources for students can be a great drain on the teacher’s own time. However, the school leadership clearly must value fostering those relationships as well. On some occasions, release time will be required in order to pursue a reciprocal responsibility you have to a community-based partner. Sometimes you have to let go a good thing because it does not allow you to get something else new or to try something different. This is hard. For example, I loved the Teacher Institute at Harvard Medical Center and the “case model” approach to learning being taught there. Later, I changed to a grade level where the Boston Public Schools had decided to go with the kit-based approach to learning. Although it is now the Speaker’s Bureau at Massachusetts General Hospital that sends scientists to share their expertise with the students, the link to Harvard still contributes. Harvard does a medical shadow day that services 120 students. It is a cool event, although it is very hard selecting who can go and who cannot.

How do you think your experiences with community partnerships contribute to the advancement of science reform?

Despite all the academic preparation that teachers must make for their profession, teachers learn little about policy. Yet powerful influences on teaching practice derive from such major policy decisions as No Child Left Behind and state testing programs. Involvement with community boards and organizations open the door not only to material resources for the classroom; they also create access to those who have influence on the making of policy. A local university received a large 5-year grant toward a 12-year project to create a new research facility. By virtue of my involvement with that university on smaller projects, I have access to people there who could invite me to speak on future uses of that facility—uses that might provide some benefit to the schools in our community and their students.

Science reform really trickles downward. Teachers can and do make change within their own environments. However, systemic change is more powerful, especially in these times when we are outsourcing many jobs because our manpower is not up to par. I am not certain why many young people see science as a challenging career. Maybe it is the math, others say it is the studying, and a few say it is the time commitment. I believe young people need to understand the power of their planning and sacrifice and the many positive outcomes that occur with a science, math, or engineering degree. Exposure plays a large role. Students need to understand what it means to have a career, and the sacrifices and the benefits that may occur. These and more need to be presented to young people as they develop and plan their futures.

If you have questions you would like to ask Darren T. Wells about

his experiences reaching out to the community, contact him at dwells@boston.k12.ma.us